By Student Whitney May

“I say to you that many times, when I did what I could, then I look into myself to understand my infirmity and [the goodness of] God who by a most singular mercy allowed me to correct the vice of gluttony. It saddens me greatly that I did not correct this weakness [myself] for love.”

St Catherine Benincasa in 1373 to a Religious in Florence[1]

Holy Anorexia

Holy Anorexia (also known as Anorexia Mirabilis or “miraculous lack of appetite”) was a phenomenon that occurred among young women during the Middle Ages. The Holy Anorexics were highly regarded as women of almost supernatural piety, and some were even canonized, or made into saints, for their dedication.

Food in the Medieval Period

Food took on a near mythic value in medieval Europe after the Great Famine of 1315-1317, when a series of cool, rainy summers led to devastating crop failure across the continent. Food prices rose exponentially, so that during the famine, a quarter of wheat, beans, or peas sold for twenty shillings, where the same amount would have sold for five shillings only two years previously. [2] Because of the abnormal moisture in the air, it was much more difficult to evaporate liquid from saltwater, leading to a shortage of salt. Without salt, meat could not be preserved, and it began to rot too quickly to be consumed.

During this period, reverent food imagery began to filter into the medieval tradition. In an article on the value of food in medieval culture, Dr. Caroline Walker Bynum, a leading scholar on food and its meaning for women in the Middle Ages, suggests that overeating became synonymous with indulging in bodily pleasures at that time. She notes the emerging presence of “magic vessels which forever brim over with food and drink” in European folktales, that the most common charity of religious orders was to feed the poor or ill, and that to share food with a stranger was “a standard indication of heroic or saintly generosity.”[3]

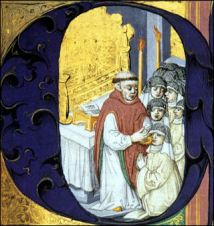

The consumption of food also represented a connection between the medieval citizen and God. The most common representation of this practice is in fact still around today, in the accepting of the Eucharist or communion bread.

So, On the Surface, Why Refuse to Eat?

You might be wondering why, if food was so important to medieval culture, some women became Holy Anorexics by refusing to eat. This is a very tricky question, and it certainly has many “right” answers. On the surface, women viewed their decision not to eat as a means of rejecting earthly pleasures in favor of a deeper connection to God; this rejection of earthly comforts is called asceticism. Holy anorexics consumed little to no food other than the Eucharist, so they believed that they were symbolically sustained by only the body of Christ.

The Holy Anorexics placed a significant value on the connection between the soul and Christ, and identified largely with the depiction of his crucifixion. Perhaps in emulation of then-popular crucifixion imagery that showed an emaciated Christ-figure, these women chose to abstain from food as a means to achieve the ultimate goal of asceticism: Imitatio Christi, or “suffering like Christ.” Holy anorexics “perceive[ed their] pain as a symbol of participation in the suffering of Christ and a means of mediating salvation to the world.”[4]

And Below the Surface?

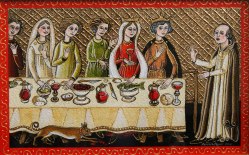

Several deeper theories exist to explain why women became Holy Anorexics. In her extensive book Holy Feast and Holy Fast, Dr. Caroline Walker Bynum notes that women were historically in exclusive control of the preparation and serving of food. In fact, courtesy at the time called for the separation of men and women at important meals. Aristocratic women, then, who did not directly contribute to the preparation of a meal would wait in nearby balconies and watch the food arrive before their menfolk. Therefore, Dr. Bynum says, decisions about whether or not to consume food were “in one sense the religious expression of social facts.”[5]

A good way to for men and women to be considered pious was through self-renunciation, or through the denying of comfort. Hebrew University nutritionists J. Griffin and E.M. Berry agree that “Self-starvation is one such form of self-renunciation,” which “grew into a prominent form of asceticism in the early to late medieval periods, particularly for women.”[6] Dr. Bynum suggests that “there is some reason to argue that women were more drawn to such fasting than men because women were especially associated with the evils of the body.”[7]

It is worth noting that Holy Anorexics such as Catherine of Siena were in effect hero-worshipped for their abstinence from food. This aligns with Dr. Sigal Gooldin’s research into anorexia as a means of achieving what she calls “heroic selfhood,” or “the process of attaching out-of-the-ordinary meanings to everyday, mundane experiences.”[8]

Medieval society was largely patriarchal, meaning its institutions were controlled by men. In a culture where the average woman had very little control over her finances, her future, her education, or even her own body, the rejection of food offered her a means to resist the patriarchal power of her society. As Dr. Bynum passionately concludes, “women’s food practices frequently enabled them to determine the shape of their lives—to reject unwanted marriages, to substitute religious activities for menial duties within the family, to redirect the use of fathers’ or husbands’ resources, to change or convert family members, to criticize powerful secular or religious authorities, and to claim for themselves teaching, counselling, and reforming roles for which the religious tradition provided, at best, ambivalent support.”[9]

Connections Between Holy Anorexia and Modern Anorexia

You’ve no doubt been wondering if Holy Anorexia is related to the modern eating disorder anorexia nervosa. There is at present no definitive answer to this question, since scholars usually find themselves divided in opinion.

Belgian psychologists Doctors Vandereycken and Van Deth proposed that fasting saints were more concerned with their interior worlds than their exterior appearances. It was not a cult of slenderness,” they offered, “but a religious-mystical cult that dominated their life.”[10]

Aligning with the work of Dr. Bynum, the celebrated social historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg suggested that Holy Anorexia symbolized the strict values of appetite control for women in the medieval age, while modern anorexia nervosa represents individualism in our time. “To conflate the two,” she says, “is to ignore the cultural context and the distinction between sainthood and patienthood.”[11]

And as Dr. Bynum herself concluded: “The twentieth-century girl refused food in order to assert control over her body; the fourteenth-century saint refused food in order to eat God and feed her fellow sinner.”[12]

Some scholars claim there is in fact a traceable connection between Holy Anorexia and anorexia nervosa. Dr. Wioleta Polinksa, chair of religious studies at North Central College, believes that women of both periods refuse food as a means to gain some control over their bodies and to achieve self-definition. She believes that: “Both groups are making the best use of the resources they have-their bodies-to define who they are.”[13]

Food Messages in Medieval and Modern Culture

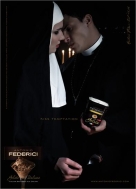

In a recent study for the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, J. Griffin and E. M. Berry turned to what most scholars believe to be a key contributor to modern anorexia—the media—and analyzed contemporary food advertisements by major brands. Their findings suggest that modern anorexics might be connected to those from the medieval period by surprisingly similar social messages about food.

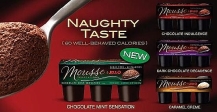

Griffin and Berry suggest that, since the image of food is still bound up so tightly with guilt, no matter the motivation of the anorexic, the aesthetic rejection of food is still equated with higher morality. Some ads, they say, create “a decided call to reject the spiritual and embrace the corporal,” while others represent “the fight of an industry against a moral internal struggle for control, the attempt to maintain self-discipline and a feeling of guilt.”[14] Have you ever seen ads that use words like “tempting,” “irresistible,” or “heavenly,” or “healthier” food alternatives that include images of halos, angelic wings, or heavenly clouds?

Check out Griffin and Berry’s article here for a few examples of their own.

Conclusion

The Holy Anorexics were a group of young women in the medieval period who rejected food both to bring themselves closer to God and to claim some control over their lives and bodies in a patriarchal culture where they had very little freewill. While Holy Anorexia and today’s equivalent anorexia nervosa might be separated by over 600 years, the motivations for rejecting food are perhaps very similar. One thing is for sure, though: as long as women live in a society that seeks to control their decisions, whether by forcing them into marriages or roles they do not want, or by telling them how to look or what kinds of food to eat, women will likely always turn to the rejection of food as a means to take control over their lives.

For Further Reading

If you’d like more information on anorexia nervosa, please visit the websites for the National Eating Disorders Association or the Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders.

Works Cited:

[1] Bell, Rudolph M. Holy Anorexia. Chicago: U of Chicago, (1985): 23. Print.

[2] Trokelowe, Johannes. Annates. Ed. H. T. Riley. Trans. Brian Tierney. Vol. 28. London: n.p., 1866. Print. Rolls.

[3] Bynum, Caroline Walker. “Fast, Feast, and Flesh: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women.” Representations 11 (1985): 2. Print.

[4] Polinska, Wioleta. “Bodies under Siege: Eating Disorders and Self-Mutilation Among Women.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 68.3 (2000): 570. Print.

[5] Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California, (1987): 192 Print.

[6] Griffin, J., and E.M. Berry. “A Modern Day Holy Anorexia? Religious Language in Advertising and Anorexia Nervosa in the West.” The European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 (2003): 43-51. Www.nature.com. The European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Web. 9 Mar. 2014.

[7] Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California, (1987): 216. Print.

[8] Gooldin, Sigal. “Being Anorexic: Hunger, Subjectivity, and Embodied Morality.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 22.3 (2008): 286. Print.

[9] Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California, (1987): 220 Print.

[10] Vandereycken, Walter, and Ron Van. Deth. From Fasting Saints to Anorexic Girls: The History of Self-starvation. London: Athlone, (1996): 221. Print.

[11] Brumberg, Joan Jacobs. Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP (1988): 45-46. Print.

[12] Bynum, Caroline Walker. “Holy Anorexia in Modern Portugal.” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 12 (1988): 244. Print.

[13] Polinska, Wioleta. “Bodies under Siege: Eating Disorders and Self-Mutilation Among Women.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 68.3 (2000): 578. Print.

[14] Griffin, J., and E.M. Berry. “A Modern Day Holy Anorexia? Religious Language in Advertising and Anorexia Nervosa in the West.” The European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 (2003): 43-51. Www.nature.com. The European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Web. 9 Mar. 2014.

You must be logged in to post a comment.