By Student Deanna Rodriguez

Biography

Christine de Pizan was the first professional woman writer in France. She was born in Venice around 1364. Shortly after her birth, in 1368, her family moved to Paris. Because of this, she’s often described as being a woman of two worlds. [1] She grew up surrounded by the French culture, but retained her Italian heritage through her familial ties. She was fluent in French, Italian, as well as some Latin, which she learned while her husband, Etienne de Castel, was the royal secretary to the court. [2] She was widowed at the age of 25, and left to fend for herself, her two children, daughter Marie, son Jean and an son who remains unnamed in records (as he likely died very early on) and her widowed mother and a niece. Almost all of her male family had left France and Christine had no relatives in Paris she could turn to him her time of distress.[3]

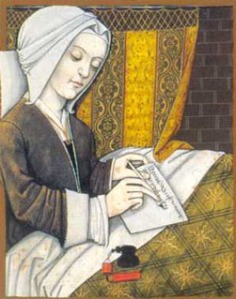

It was through her literacy and writing that she was able to turn her luck around and provide for her family. Her first literary contacts were “in the frivolous court, where writing poetry was one of the principle social accomplishments.”[4] Christine explained that her change of fortune after her husband’s death obligated her to “become a man” and take on a man’s responsibility. She explores this further in The Book of the Three Virtues by saying that widows must “be constant, strong, and wise… not crouching like a foolish woman in tears and sobs without any defense, like a poor dog who cowers in a corner when all others attack him.” [5] Pizan’s way of staying strong was through her writing, and it was because of her literary circles, where her poetry was being read and appreciated, that she met a noble Englishman, the Earl of Salisbury, who offered to take her son Jean into his household in England as a companion for his own son, securing his future as the earl was especially favored by Richard II’s court. Her daughter was given the opportunity to enter the royal Dominican covent in Poissy as part of a dowry from King Charles VI’s own daughter entering the order. [6] It’s unknown for certain how she supported herself while writing, but clues from not only her writing but from illustrations of her hint that she was most likely employed through some kind of government source, most likely because of her ties remaining from her husband. She was not only a skilled writer, but her manuscripts indicate that she wrote in a cursive script that was used in the correspondence of the royal chancellery, and was as well familiar with the official language of the chancellery, frequently making use of a formula such as “I, Christine” and making sure to mention definite dates and to call people by their official titles. You can see these characteristics particularly in some of her more serious works like The Deeds and Good Customs of the Wise King Charles V, Christine’s Vision, and The Book of Peace.[7] As the century progressed, the instability of life in France began to take its toll on Christine who joined her daughter in the Abbey of Poissy. She continued to write for a while longer while at the Abbey, and her final work La Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (The Tale of Joan of Arc) was written in July of 1429. She was 65 when she retired from writing and it is not known when exactly she died or where.

but her manuscripts indicate that she wrote in a cursive script that was used in the correspondence of the royal chancellery, and was as well familiar with the official language of the chancellery, frequently making use of a formula such as “I, Christine” and making sure to mention definite dates and to call people by their official titles. You can see these characteristics particularly in some of her more serious works like The Deeds and Good Customs of the Wise King Charles V, Christine’s Vision, and The Book of Peace.[7] As the century progressed, the instability of life in France began to take its toll on Christine who joined her daughter in the Abbey of Poissy. She continued to write for a while longer while at the Abbey, and her final work La Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (The Tale of Joan of Arc) was written in July of 1429. She was 65 when she retired from writing and it is not known when exactly she died or where.

Works

Around 1394, four years after the death of her husband, Christine began to write poetry. Christine herself speaks of 1399 as the gate her literary career began. [8] By 1400, her poetry was starting to be known beyond the limits of French court circles and even as far way as England and the Visconti court in Milan. Pizan was quick to mention in Christine’s Visions that her notoriety was “because poetry written by a woman was such a novelty.”[9] Christine de Pizan stood out because while there were texts out there for women, women wrote not many and they detailed women’s roles the way men saw them. Christine, on the other hand, writes about what the roles actually were as opposed to what patriarchal society wished them to be: she “provides an accurate picture of the full range of women’s responsibilities within the familial, social, political, and economic spheres”[10] Looking at Christine de Pizan’s works gives a special insight into medieval women’s lives not typically found because of the agency she acquired from her writing.

Texts

The Book of The City of Ladies

The Book of the City of Ladies is Christine’s respond to a complaint she made in God of Love’s Letter, that women had not written books about themselves and were, therefore, represented unfairly over many centuries. As Christine peruses books in her own library, she becomes painfully aware of the bad treatment women had experienced at the hands of authors. She is approached by three allegorical ladies, Reason, Rectitude, and Justice and charged her with establishing a new written tradition of women by building the City of Ladies, where the debris that needs to be cleared from the building site stands for the writing of the anti-feminists and where every stone is a celebrated woman of learned or military achievement and where the inhabitants are women of impeccable virtue.[11] For more information, click here.

This text serves as a sequel of sorts to Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies, as it takes place after the city has been created. The three virtues again appear to Pizan and have her write a handbook for the women in the society– not in the idealized society but that one that existed in Christine’s own time.[12] She discusses how a woman should act in society; treat her husband, and goes into even widowhood, which was a big deal to Pizan. To find out more about this text, click here.

Christine’s Vision

This work is considered the principle source for her biography. It follows the genre of Visions. In medieval times, the genre of visions had political and moral contents, and Pizan’s was no different. She leads with an allegorical version of her own birth, and shows the reader the origins and current state of France. Christine treats her Visions as a interior journey, where she hopes to find meaning for her country and her own life by reviewing past successes and failures with the help of authoritative allegorical figures. To find out more information, click here.

This was written between 1404 and 1407, and is focused more on teaching virtues to a prince; similar to the way she does in Letter from Othea. She takes up the image of society as a body in which every part has its specific function and duties. Christine constructs a tripartite work in which she addresses first the prince (the head), then the knights and novels (the limbs) and finally the common folk (the feet). To find out more information on this text, click here.

The Book of Peace

The writing of this text reflects the troubled political climate of France at the time. Christine began writing it on September 1, 1412, when peace between two warring factions seemed to be occurring. When that failed, she picked up her pen again September the following year, and wrote books 2 and 3 of the text.[13] To find out more about this text and this historical context surrounding it, click here.

This text was written after Christine had fled from Paris to the Abbey of Poissy, where her daughter resided. This text was mostly considered a religious meditation on Joan of Arc as a figure, as Christine died well before Joan’s fall from grace. This was to be Pizan’s last work published and distributed.

Poetry

Christine wrote a ton of poetry and thus, it would be impossible to collect everything she wrote down for discussion, so we will look at what can be considered her noteworthy work:

“One Hundred Ballads”

In her early poetry career, Pizan mostly wrote to “distract her mind from her troubles and her sorrows” and she also wrote love poetry which she described as “singing joyously with a sad heart”. By 1403, she had written enough to assemble her poetry into a collection, which she titled One Hundred Ballads. She created thematic groups within the cycle: poems of widowhood, the development of a love relationship from the point of view of the lady, and another love story where both knight and lady speak. Some poems deal with mythological topic, give some sort of moral instruction or accuse false lovers; some allude to current events or are addressed to a specific patron. Many of the themes in her later works can be seen already present in this first collection. [14] To read some poems from this collection, click here.

“One Hundred Ballads of a Lover and a Lady”

Despite having moved on to more serious forms of writing, Christine took much joy in composing love poetry and in 1410, Cent Ballads d’Amant et de Dame (One Hundred Ballads of a Lover and a Lady), the last of her lyrical poetry was copied into a beautiful manuscript, and was even presented to the queen, as seen in the painting to the right. [15]

Despite having moved on to more serious forms of writing, Christine took much joy in composing love poetry and in 1410, Cent Ballads d’Amant et de Dame (One Hundred Ballads of a Lover and a Lady), the last of her lyrical poetry was copied into a beautiful manuscript, and was even presented to the queen, as seen in the painting to the right. [15]

In the beginning of the work, the first twenty-five poems, examines the emotions of a lady who first resists and then succumbs to the advances of her lover. The middle section explores their romance, while the last section show a theme that is common in Pizan’s work, the belief that society obligated a women to pay far too high a price for any momentary pleasure experienced from love outside marriage.[16] To read some poems from this collection, click here.

“Love Debate Poems”

– Le Livre du Debate de duez amans

– Le Livre des Trois judgemens

– Le Livre du Dit de Poissy

Letters

Christine was a prolific letter writer and she used letters not only for persuading public figures to be more responsible in public affairs but also for literary purposes.

“L’Epistre au Dieu d’Amour” (“Cupid’s Letter”)

Often referred to as “The God of Love’s [Cupid’s] Letter”, it was one of the longer literary works that first established Christine’s reputation as a professional woman of letters. It is in the form of an epistle, one dictated by Cupid, in his capacity as king of the court of love, to all loyal lovers everywhere. At the same time, Christine’s poem is part of her extended polemic against what she perceived to be the fundamental misogyny of the Romance of the Rose. It should be read as already participating in the “Debate on the Romance of the Rose”.[17]

“L’Epistre de la Prison de Vie Humanie” (A Letter concerning the Prison of Human Life)

This letter was in response to one of the greatest disasters for the French during the Hundred Years’ war. In approximately three hours, the flower of French chivalry was either killed or imprisoned by the English. This text was one that Christine addressed to the people who lost family members at the batter. IT was intended as a consolation. It is one of her most spiritual and edifying texts, offering philosophical and Christian arguments in order to console grieving ladies. It was that same year, 1418 that Christine fled from Paris, never to return.[18]

“Epitre d’Othea” (Othea’s Letter or Epistle of Othea to Hector)

A few years after writing this, Pizan realized that this was a turning point in her literary career. Not only not only the court in France, but England was reading her as well, and by male audiences. The Letter is in intricate and extremely learned text in the tradition of the “mirror of prices” or of courtesy books. Each chapter is dived into three parts: text, floss, and allegory. For the first two parts, Christine draws on Ovidian mythology, and on the Histoir ancienne jusqu’a Cesar (Ancient history up to Julius Caesar). In the Letter, Christine presents each fable in a succinct four lines then explains its plot or contents in a literal or historical interpretations, then she draws on a moral on correct chivalric behavior from each story. [19] To find out more about this letter, click here.

Feminist Legacy

Christine de Pizan had often mentioned in her writings that she hoped to be well known for her writing ability and for her works to live on after her.

Influence

Christine’s literary influence has been immense: “many influential women of the next generation owned and read copies of de Pizan’s work including Marguerite of Austria and Mary of Hungary, two future governors of the Netherlands of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V; Louise of Savoy, regent of France during the minority of Francis I; Anne of Brittany, twice queen of France, and Queen Leonor of Portugal”[20] The very thought of an extended readership like this would have made Christine extremely happy as she’s stated:

“And to this end I thought that I would multiply this work in various copies throughout the world … so that it can be presented in various places to queens, princesses, and noble ladies … that through their efforts it may be circulated among other women” [21]

You can also see her influence in Simone de Beauvoir who stated that “Épître au Dieu d’Amour (Cupid’s Letter)” was “the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex”[22] Christine de Pizan definitely made an impact, being the first European woman to make a living writing, and there’s no denying that her works still have an effect and are relevant today.

Works Cited and Consulted

Photo 1: http://bcm.bc.edu/issues/winter_2010/endnotes/an-educated-lady.html

[1] Willard, Charity Cannon. Christine De Pizan: Her Life and Works. New York, NY: Persea, 1984. Print. (pg15-31)

[2] Redfern, Jenny. “Christine De Pisan and “The Treasure of the City of Ladies”: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric.” Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women in the Rhetorical Tradition. Ed. Andrea A. Lunsford. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh, 1995. N. pag. Print.

[3] Willard (39)

[4] Willard (42)

[5] De Pizan, Christine. The Selected Writings of Christine De Pizan: New Translations, Criticism. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. New York: W.W. Norton &, 1997. Print. (170)

Photo 2: http://www.nndb.com/people/835/000107514/

[6] Willard (43)

Photo 3: Christine de Pizan, British Museum, MS Harley 4431, f.– c. 1411

[7] Willard (47)

[8] Willard (44)

[9] Willard (51)

[10] Bornstein, Diane. The Lady in the Tower Medieval Courtesy Literature for Women. Hamden: Archon Books, 1983 (120)

[11] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (117)

Photo 4: http://www.uweb.ucsb.edu/~kstaples/gallery.html

[12] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (155)

[13] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (201)

[14] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (5)

Photo 5: http://profiles.arts.monash.edu.au/karen-green/papers/

[15] Willard (54)

Photo 6: http://maidjoan.tripod.com/ditie.html

[16] Willard (61)

[17] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski ( 17)

[18] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (249)

[19] Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (29)

[20] Sunshine for Women. Feminist Foremothers 1400 to 1800. 12 April 2001.

[21] Willard (221)

[22] Schneir, Miriam. “Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings”. Vintage Books. (xiv)

You must be logged in to post a comment.